The prefix “design” in the name of my job does a lot of legwork to create a false image of what modern designers are supposed to be.

When you hear someone talk about designers, usually your first instinct is to imagine a trendy young man hunched over an iPad who can’t find a color he likes.

Actually, designers have long since evolved from these primitive — by modern standards — life forms into a form of homo designicus.

(Okay, this name sounds terrible, but bear with me.)

Modern designers are psychologists 75 percent of the time; only instead of couches and Rorschach inkblots, they use focus groups, surveys, and heuristic evaluations.

Also, where psychologists generally tend not to use their knowledge for personal gain, we designers don’t bind ourselves with any Hippocratic oaths.

What we learn about the user gets instantly incorporated into our development cycles.

In this article, I will cover the basics of design mindset first, and then guide you through the minefield of more advanced topics.

So if you start reading this article with an enlightened look and end up with a look of bewilderment, it is by design (no pun intended).

Learn also about our design services.

Emotional Design: Can I Borrow a Feeling?

The work of your typical designer is centered around understanding users’ needs and eliciting specific responses. Their job isn’t that far off from Pavlov’s experiments with dogs in many ways.

(If you take offense at this comparison, you’re barking up the wrong tree.)

The responses we have to our surroundings are seldom entirely rational. There is a significant emotional component to how we experience the world.

Designers distinguish between three tiers of emotional responses:

- Visceral, which is our first gut reaction.

- Behavioral, which is a subconscious reaction.

- Reflective, which is a conscious assessment.

Emotional design, therefore, is a design that anticipates and accommodates all three of these reactions.

The term “emotional design” was coined by Aarron Walter in his book Designing for Emotion. In it, he heavily borrows from Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs and marries it with user experience.

Maslow’s initial model described the necessity for having a person’s most basic demands met before they can seek out increasingly more abstract needs.

To put it simply, a hungry person finds no comfort in spiritual self-reflection. Physiology trumps everything.

Likewise, Walter’s pyramid of user needs creates a bottom-to-top hierarchy of utilities that a design needs to meet to elicit a positive emotional response.

First, we want the design to be functional. Does the product or service fulfill its primary objective?

This is the foundational question that makes or breaks the product before it’s had its chance to shine. A mug can look nice and feel good in the hand, but if it cannot hold water, the product is dead on arrival.

Next, the design needs to be reliable. Can we trust the product to keep working?

This is where many man-hours are spent as products go through rigorous tests. If we were to continue with the mug analogy, we need to be sure that it won’t break suddenly when we drink from it.

Then, the design needs to be usable. Can a person figure out the product with minimal guidance?

This is where, for example, childproof caps both excel and fail: their specifically obtuse design keeps drugs out of children’s reach, but it takes the adults a few tries to open them, too.

Only when the design is functional, reliable, and usable can it become pleasurable. This is where a design goes beyond the simple utility and finally develops a personality.

Now, personality is inherently flawed as it doesn’t speak equally to everyone, but it’s what makes products memorable, even if at a small cost.

The prevailing belief is that designers — i.e., painters of pretty pictures as per most people’s understanding — only come into play at this last stage. However, the consideration for the first three qualities of a design is far greater.

On a day-to-day basis, designers deal with raw data more often than they do with the vector graphics editor Figma.

Triple Diamond: Turning Uncut Gems into Jewels

Another common misconception is that inspiration is something that catches us with our metaphorical pants down.

It is not.

True creativity is not bogged down by a methodical approach and rarely waits for the muse. Quite the opposite, creative professionals are best described as “keen analytical minds” rather than “head-in-the-clouds dreamers.”

One British independent charity called Design Council conducted a study of vastly different companies — the list included Microsoft, Starbucks, and even LEGO. The Council found that, regardless of the company’s industry, people working there seek creative solutions in essentially the same way.

The name for this framework differed in each company, but the underlying concept was the same: there are four distinct phases to solving a design problem.

- Discover: understand the issue.

- Define: filter through and elaborate on the data you found.

- Develop: find potential solutions.

- Deliver: test out solutions at a small scale, and improve those that work.

The two diamonds that became this model’s namesakes — Double Diamond — represent a process of exploring a design issue on a wide scale first, then narrowing it down and taking focused action.

The Double Diamond is a framework that can be applied to almost any industry where problem-solving is required, not just product design.

I’m only telling you all of that so we can move on to my next point: the Double Diamond is an already outdated, if still effective, model.

That’s the thing about us designers; we have a pathological need to innovate something, even if it’s the very thing that helps us innovate in the first place.

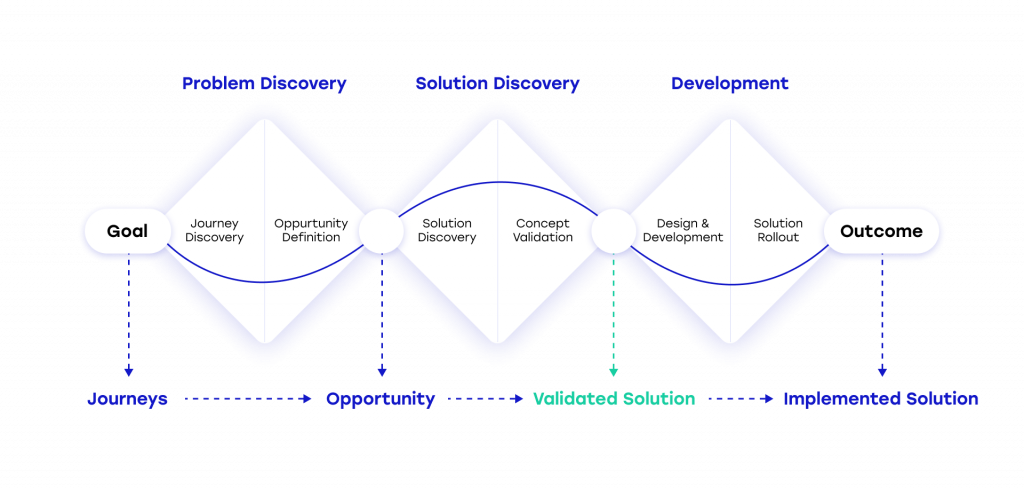

What comes after the Double Diamond?

The answer may surprise you — it’s theTriple Diamond.

If the first diamond focuses on the why and the second diamond on the what, the third diamond is all about the how.

While the design process within the Double Diamond framework stops at a prototype, the Triple Diamond invites designers to iterate on their solutions. The internal validation with the team and stakeholders is substituted with external validation with customers.

Some designers even make a point to distinguish service design from the design of services: the latter is inherently user-centric, and the entire development cycle is sparked by user insight.

This last third diamond is effectively a stage of discovery where designers learn a lot about the product, its strengths, and potential weaknesses. They fill in more details through usability tests and stay flexible to allow for change.

Turning Design Thinking into Design Doing

Speaking of tests, the heading above clearly didn’t go through focus groups. Otherwise, it wouldn’t sound like a caveman’s approximation of English.

The Design Thinking we’re talking about here is a comprehensive problem-solving framework.

Design Thinking is observational. It involves analysis and research — and lots of it. A common slogan associated with Design Thinking is, “plan for complexities to design for simplicity.”

As the name suggests, Design Doing is the practical application of Design Thinking. Or in other words, it is Design Thinking with a bias for action.

Design Doing is experiential and involves a lot of playing by ear. Its most significant takeaway is that you can learn more from prototyping, especially failed prototyping, than from conducting half a dozen surveys.

The creative confidence needed not to be afraid of discarding prototypes is what IBM, a big proponent of Design Thinking, summarizes with the “design early, design right” motto.

IBM believes that you will face fewer consequences the sooner you understand when a design doesn’t work. The flexibility for change is not constant and decreases over time as more code is written.

Therefore, the costs and the effort incurred by having to redesign from scratch grow exponentially with each new project phase. They are negligible at the design phase but scale up as you approach release.

Design Doing allows us to mitigate risks throughout the development life cycle.

On Internal and External Design Teams

Since we’ve busted some myths already, it’s time to talk about the big one.

The idea we often encounter and rarely contest is that a business needs to be self-reliant, like a country besieged by enemies.

The first thing many startups do once they proceed to Series A funding is to get their own sales, marketing, and design teams.

We all know the wisdom behind the “jack-of-all-trades” term, yet its meaning escapes us when we’re discussing self-sufficient companies.

The solution that we at Helmes propose is simple — use an external development team instead of an internal one.

By the virtue of being hired outsiders, an external team (a design team, in my case) has the pull that an internal team can often only dream of.

It is clear early on whether the company at large is receptive to change. New processes are something one cannot force upon the entire organization.

All you can do is help them adapt to it and lead by example.

Roughly 99 percent of design projects are communication projects. There’s constant clarifying and explaining the input between different teams to achieve common goals.

The old “the artist vs. the engineer” dilemma doesn’t have to rear its ugly head when both sides operate from a design, user-oriented mindset.

This sounds incredible, but it takes a lot of effort to get there in reality. The road to it is paved with asking lots of questions; that’s something designers have a bias for.

There is a saturation point after which asking too many questions can be harmful, but most design researchers never reach this point.

It helps to have an outsider’s perspective. Rather than simply complete their design tasks, the Helmes team seeks to “shape the organization from the inside.”

As we’ve already covered, Design Thinking and Design Doing are, first and foremost, problem-solving frameworks. They work just as well for engineers as they do for designers.

The work of an external design team parallels the change in a designer’s role as a whole. While it used to deal exclusively with tangible products, now it’s more complex. Philosophical, even.

The goal of design partners is to be missionaries of a new design mindset.

Get in touch